Michelle Antonorsi

Degree project blog page

https://commons.pratt.edu/degreeprojectmagic/michelle-antonorsi-dream-space-up-side-down-manhattan/

Dream | Reality

The two terms are often thought to oppose each other, but in their juxtaposition, it becomes increasingly difficult to draw a dividing line. Where does the boundary lie between sleep and wake, fantasy and reality, dream and nightmare? If reality is a construct of our brain’s interpretation of sensory input, then a dream is only different in its lack of physical stimulation. It is uprooted from the limitations of matter; liberated through its confinement to the mind. It is symbolic and literal, temporal and infinite, reflective and predictive. It is a collage of memories and an expression of desires. It is an isolated universe as much as an extensive network of space and time. It is everywhere and nowhere. As a world within a world, it is a heterotopia.

In a society that is increasingly replacing critical thought for automated perception and disengaged doing, the dream, or in this case, the daydream, provides a means of escape rather than a means of inspiration. It allows humans to tolerate the banality of daily activities; even though our bodies may be physically positioned somewhere for example, in a factory, performing a repetitive task, our minds frequently float elsewhere, generating fantasies which become a means for tolerating the dull activity. It is because of this absence of engagement that the daydream emerges, but rather than productive inspiration, it is a missed opportunity of the alienated labor process that inhibits actual fulfillment. If our realities were not so detached, then the mind might not be so drawn to wonder and rather be encouraged to stay within a space and engage in actively perceiving, experiencing, creating and in this way fulfilling its desires. Alienation is a product of society’s inability to satisfy our need for self expression and exploration of desires, that keeps our dreams as dreams rather than encouraging the collaboration of our imaginations and realities.

Dreams are beautiful phenomena, but they are inherently isolating. They are heterotopias abiding by the non-rules of unreality, disconnected from the physical stimuli that allow us to share and connect through experience. Dreams can become alienating when they are not feeding back to reality; to live within a dream or sleep through daily life is to miss the potential to materialize our fantasies and connect with others. Why should our dreams be confined to the world of our minds when they have the capacity to engage with and enrich our realities? If architecture is to address this alienation, it must engage with and synthesize these contradictions and encourage the imagination and reality to influence each other rather than be a means of tolerating unfulfilling activities.

In a society that is increasingly replacing critical thought for automated perception and disengaged doing, the dream, or in this case, the daydream, provides a means of escape rather than a means of inspiration. It allows humans to tolerate the banality of daily activities; even though our bodies may be physically positioned somewhere for example, in a factory, performing a repetitive task, our minds frequently float elsewhere, generating fantasies which become a means for tolerating the dull activity. It is because of this absence of engagement that the daydream emerges, but rather than productive inspiration, it is a missed opportunity of the alienated labor process that inhibits actual fulfillment. If our realities were not so detached, then the mind might not be so drawn to wonder and rather be encouraged to stay within a space and engage in actively perceiving, experiencing, creating and in this way fulfilling its desires. Alienation is a product of society’s inability to satisfy our need for self expression and exploration of desires, that keeps our dreams as dreams rather than encouraging the collaboration of our imaginations and realities.

Dreams are beautiful phenomena, but they are inherently isolating. They are heterotopias abiding by the non-rules of unreality, disconnected from the physical stimuli that allow us to share and connect through experience. Dreams can become alienating when they are not feeding back to reality; to live within a dream or sleep through daily life is to miss the potential to materialize our fantasies and connect with others. Why should our dreams be confined to the world of our minds when they have the capacity to engage with and enrich our realities? If architecture is to address this alienation, it must engage with and synthesize these contradictions and encourage the imagination and reality to influence each other rather than be a means of tolerating unfulfilling activities.

Concept Statement

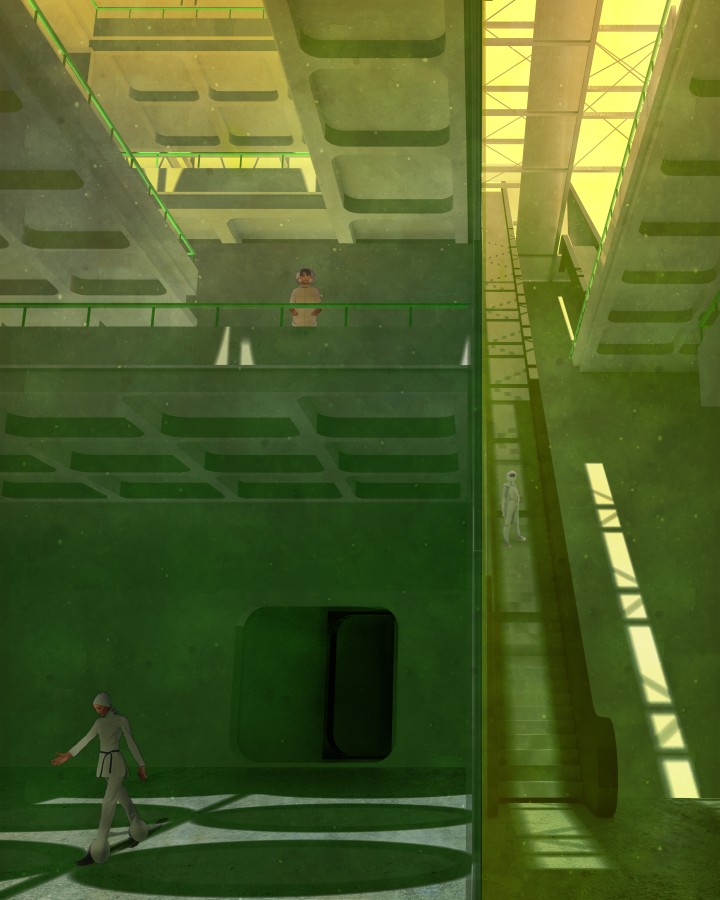

By architecturalizing industry through the integration of energy infrastructures and public spaces, architecture has the opportunity to design light to create dream spaces that encourage a more active engagement with experience as well as a more conscious consumption of energy through a total experience of light.

Project Statement

The industrialization of society has alienated humans from their modes of production, the products of their production, as well as themselves and each other. This can be attributed to the ultra commodification of environments and the absolute focus on efficiency and productivity that is experienced in many aspects of life. The resulting is an impoverishment of perception in which the human is generally disengaged from his/her environment. This diminishes the quality of the product as much as the experience of the human, resulting in the production and endless reproduction of empty objects, empty people, and empty spaces. The difficulty of this condition is that the fulfilment of human creativity, dreams, and desires opposes the efficiency and productivity of society. Dreams are not considered productive in a directly quantifiable sense and are therefore generally left out of the discourse. But juxtaposing the contrary objectives of dreams and productivity can expose their relationship and reveal a way to synthesize the two.

As the world is haunted by the lurking shadow of climate change, the subject of energy continues to be a central topic, and power plants continue to be key players. A focus on efficiency has led to a complete separation of energy industries from city infrastructures. This has pushed power plants to the countryside and allowed people to believe that they can simply flip a switch and the lights go on, like magic. However efficient this may be, it has led people to forget the true work involved in the production of energy and therefore its true value. This dissociation begs us to reconsider the future of electricity and our relationship with light. By architecturalizing industry through the integration of energy infrastructures and public spaces, architecture has the opportunity to design light to create dream spaces that encourage a more active engagement with experience as well as a more conscious consumption of light.

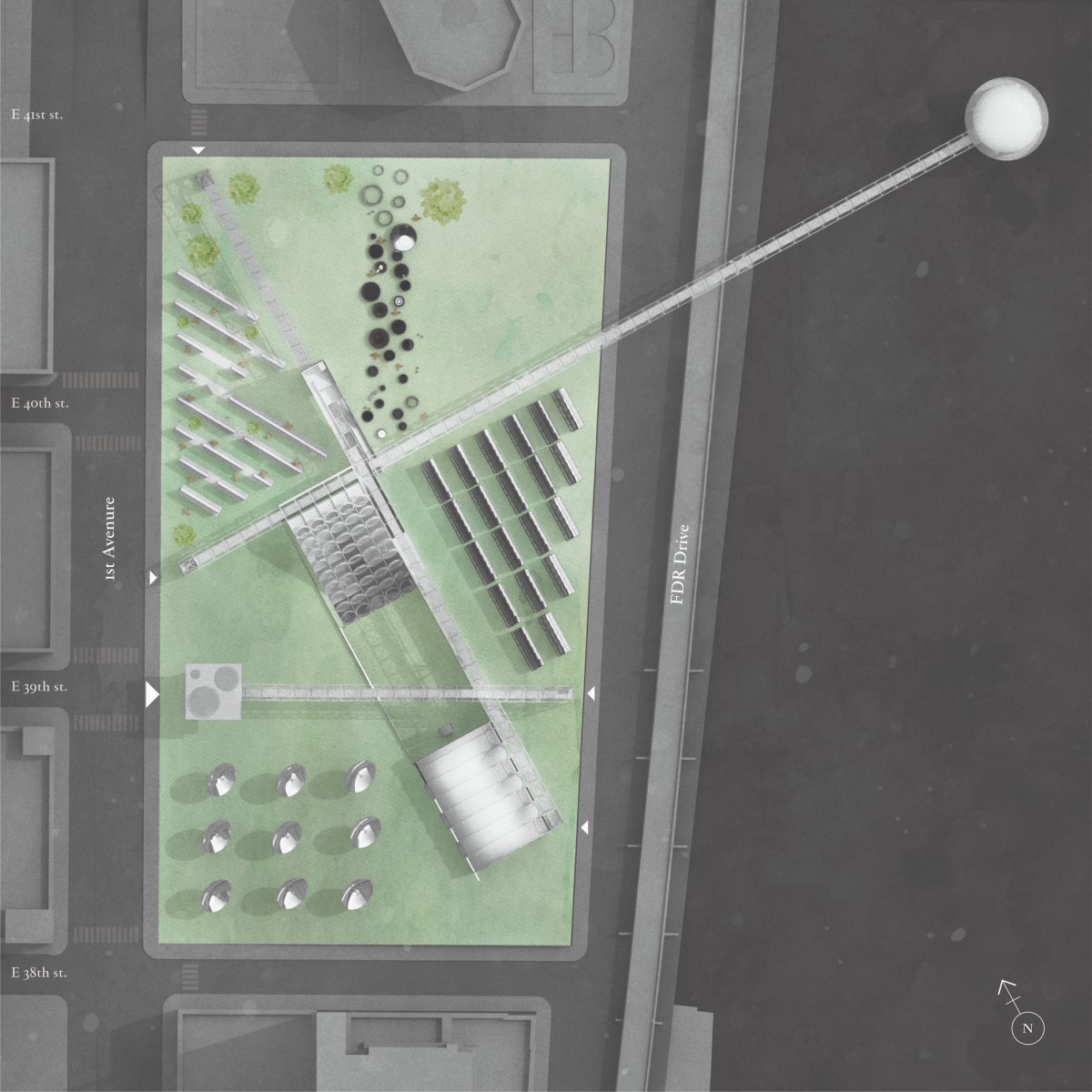

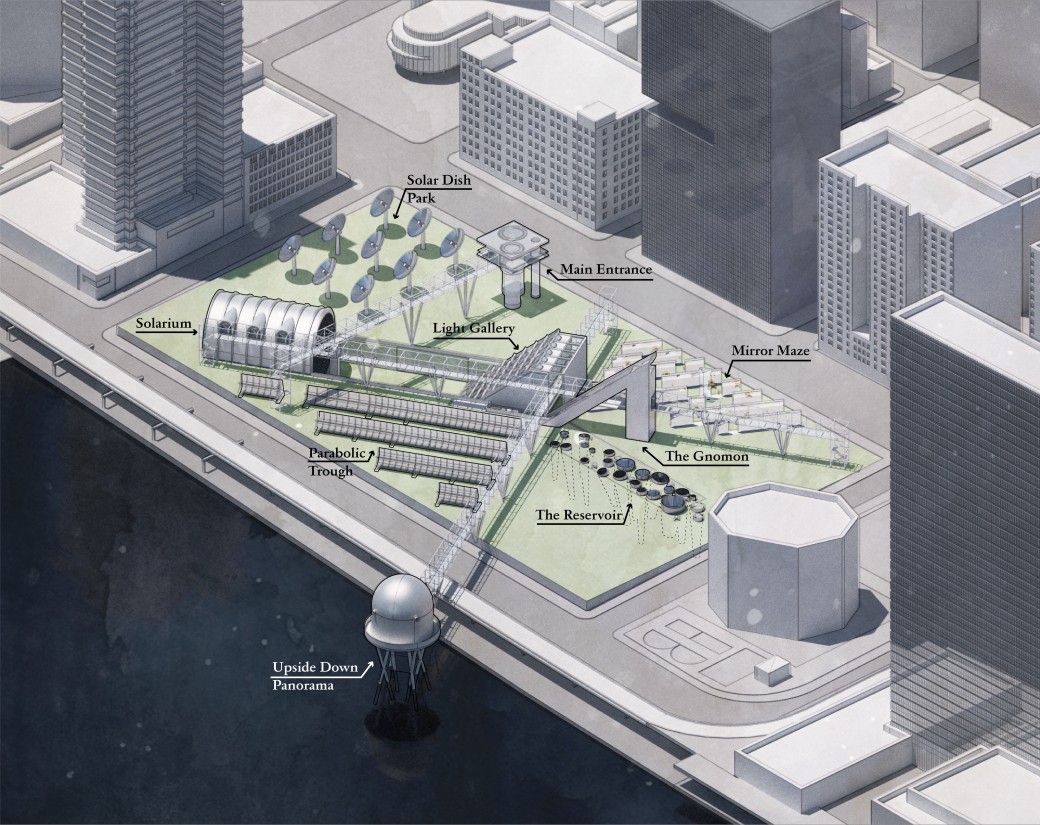

Famously known as the city of lights, New York was one of the early cities to be artificially illuminated. It now consumes an average of 11,000 Megawatt-hour per day and less than 1/4 of it comes from renewable sources. The historic Waterside Generating Plant, between 39th and 42nd St. on the East River, was one of its first steam power plants. What was once a center of energy, and a symbol of industry and technology, has now been decommissioned and completely demolished to make room for the development of what is planned to be more luxury residential towers.

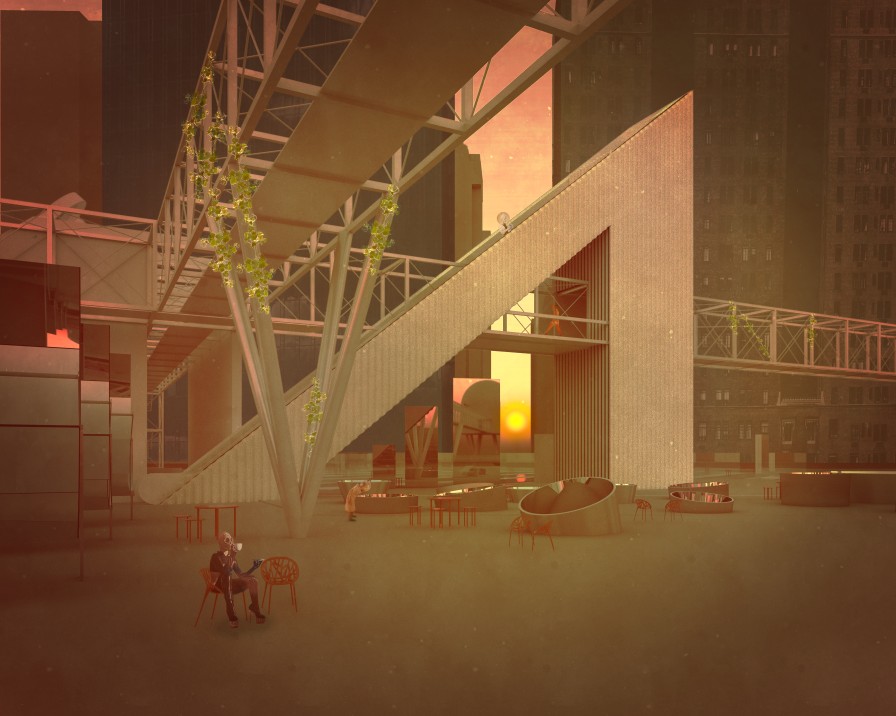

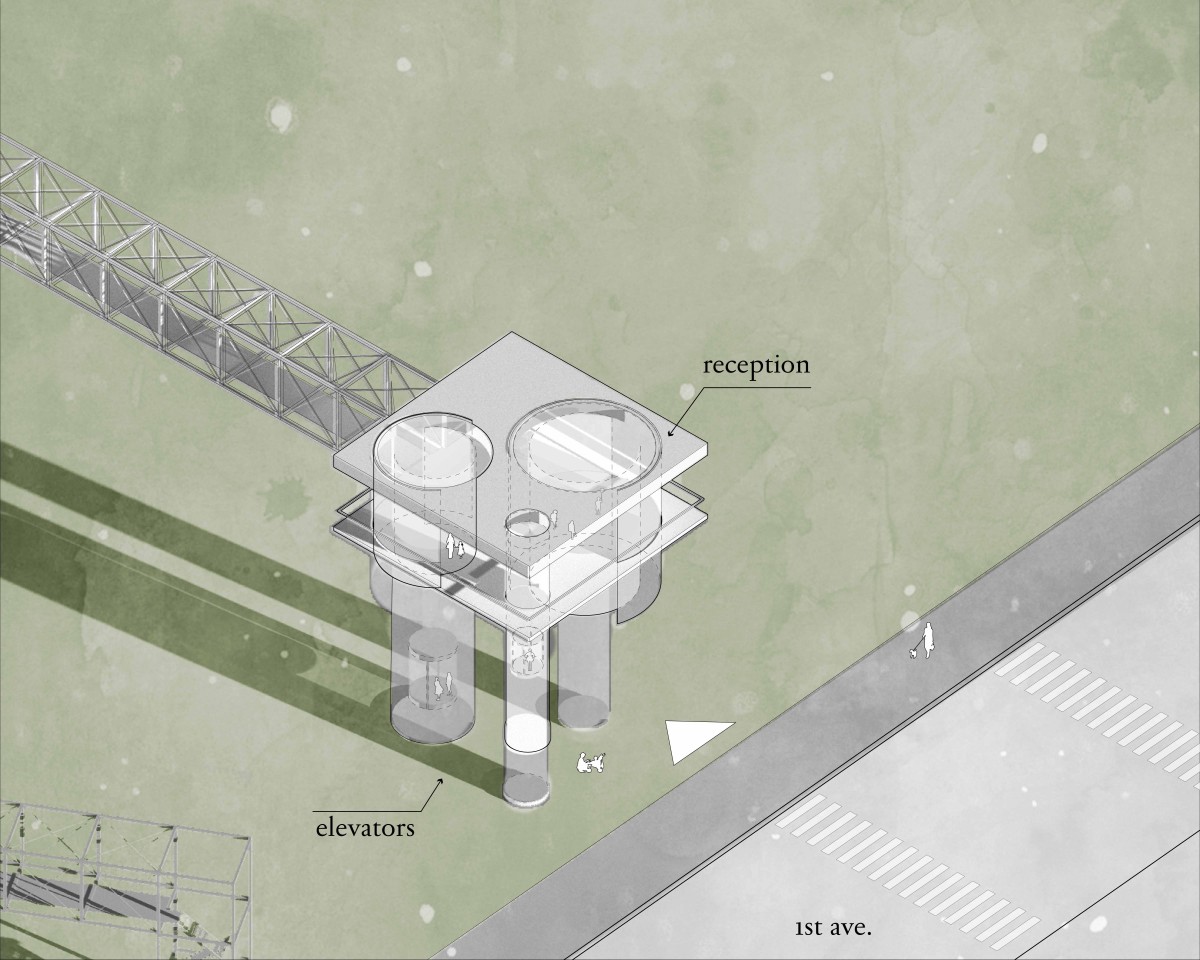

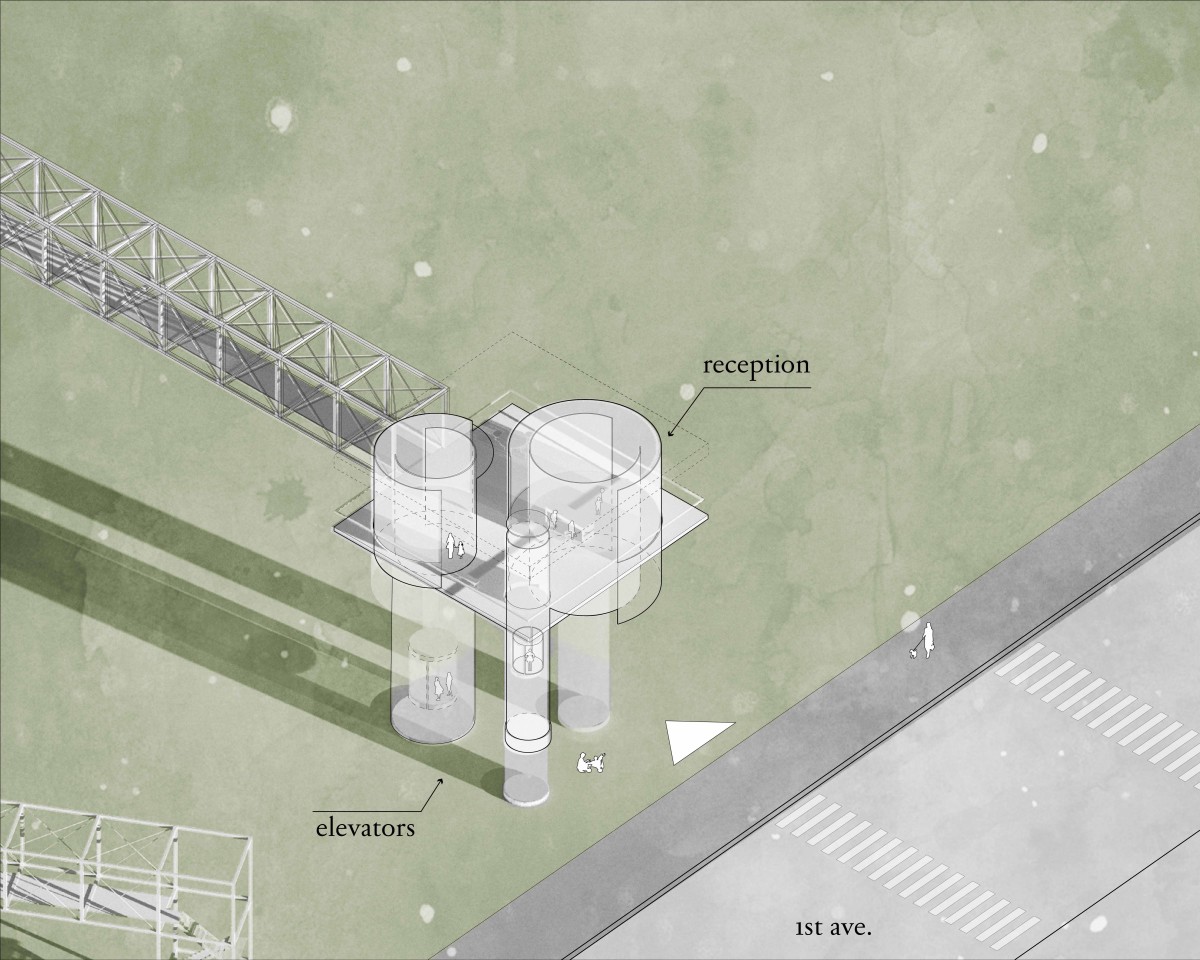

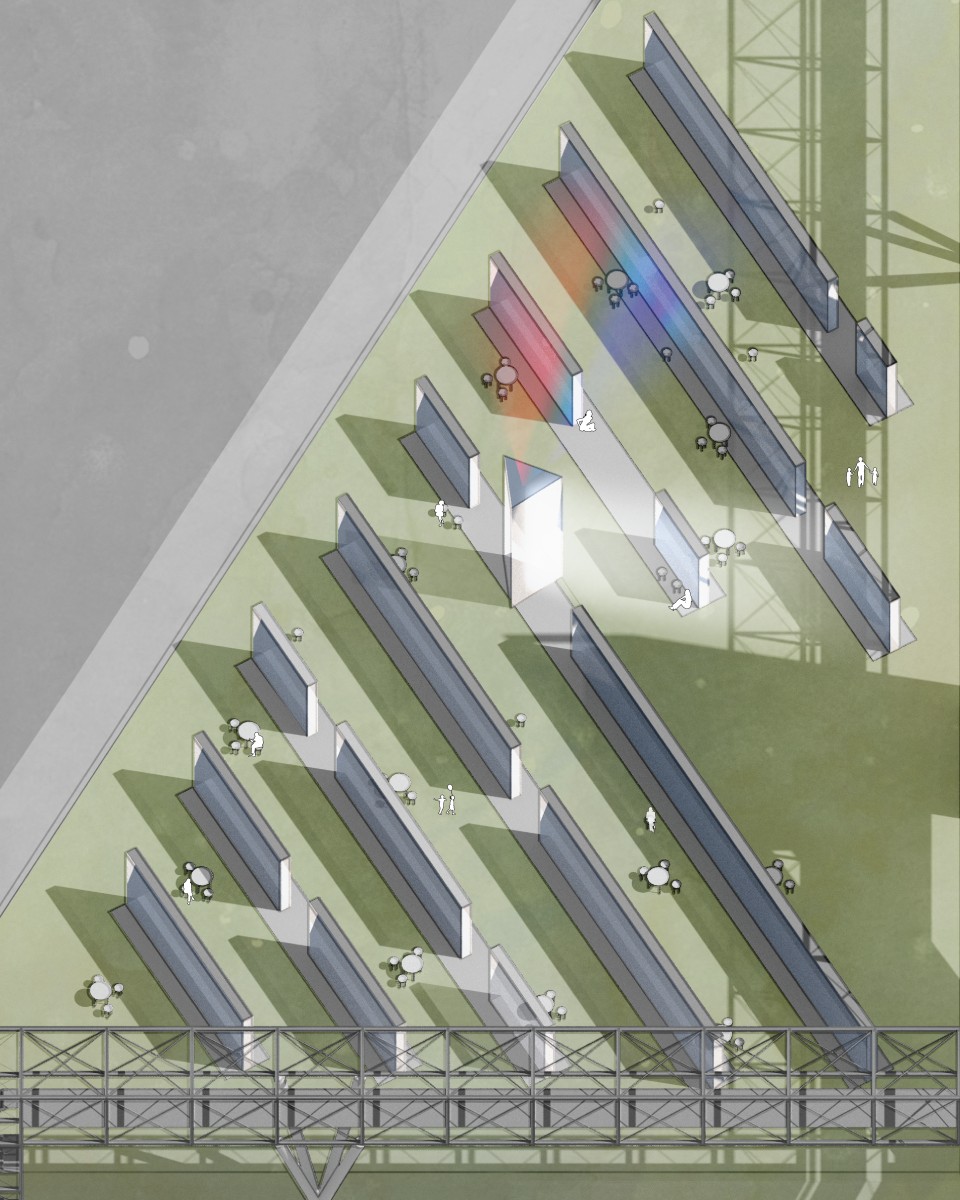

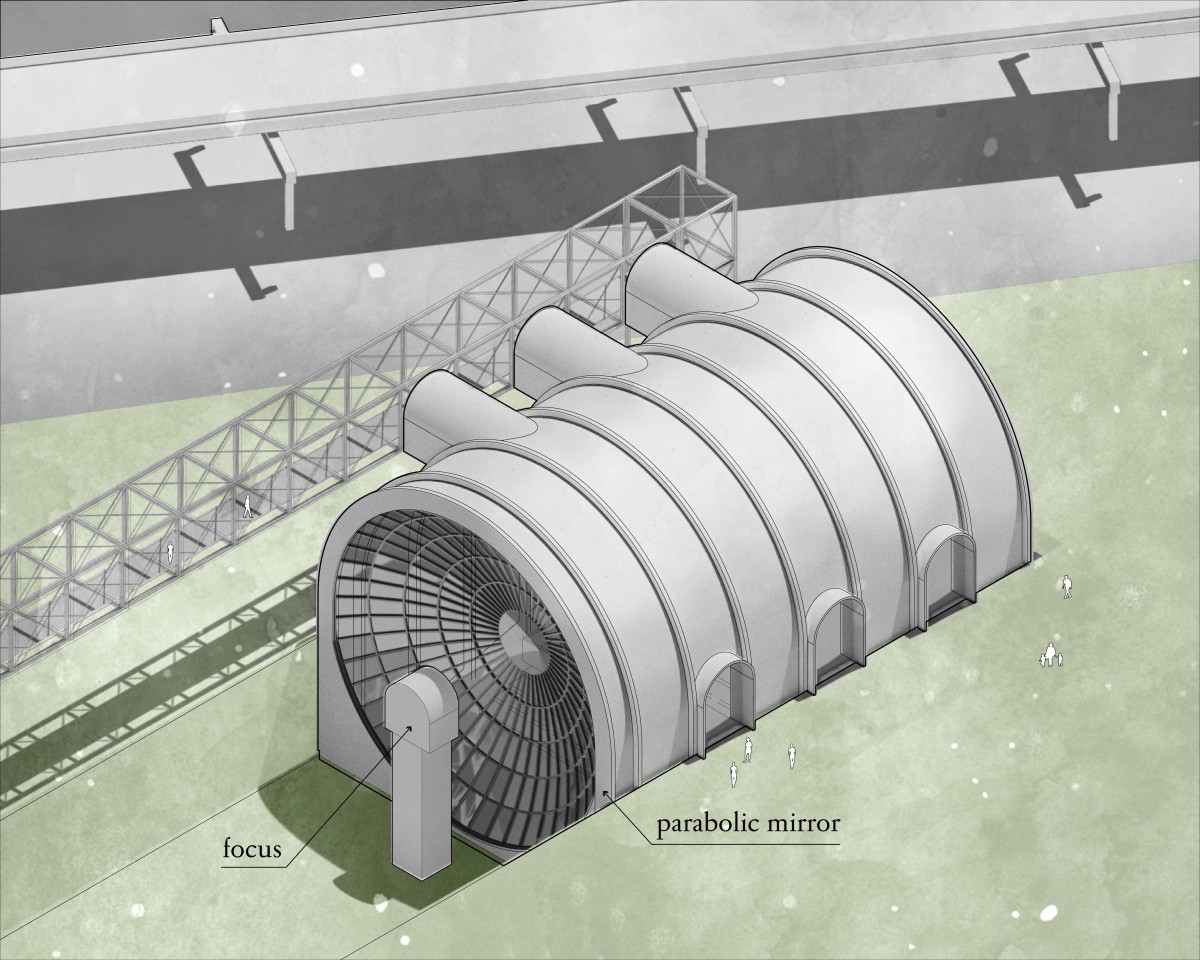

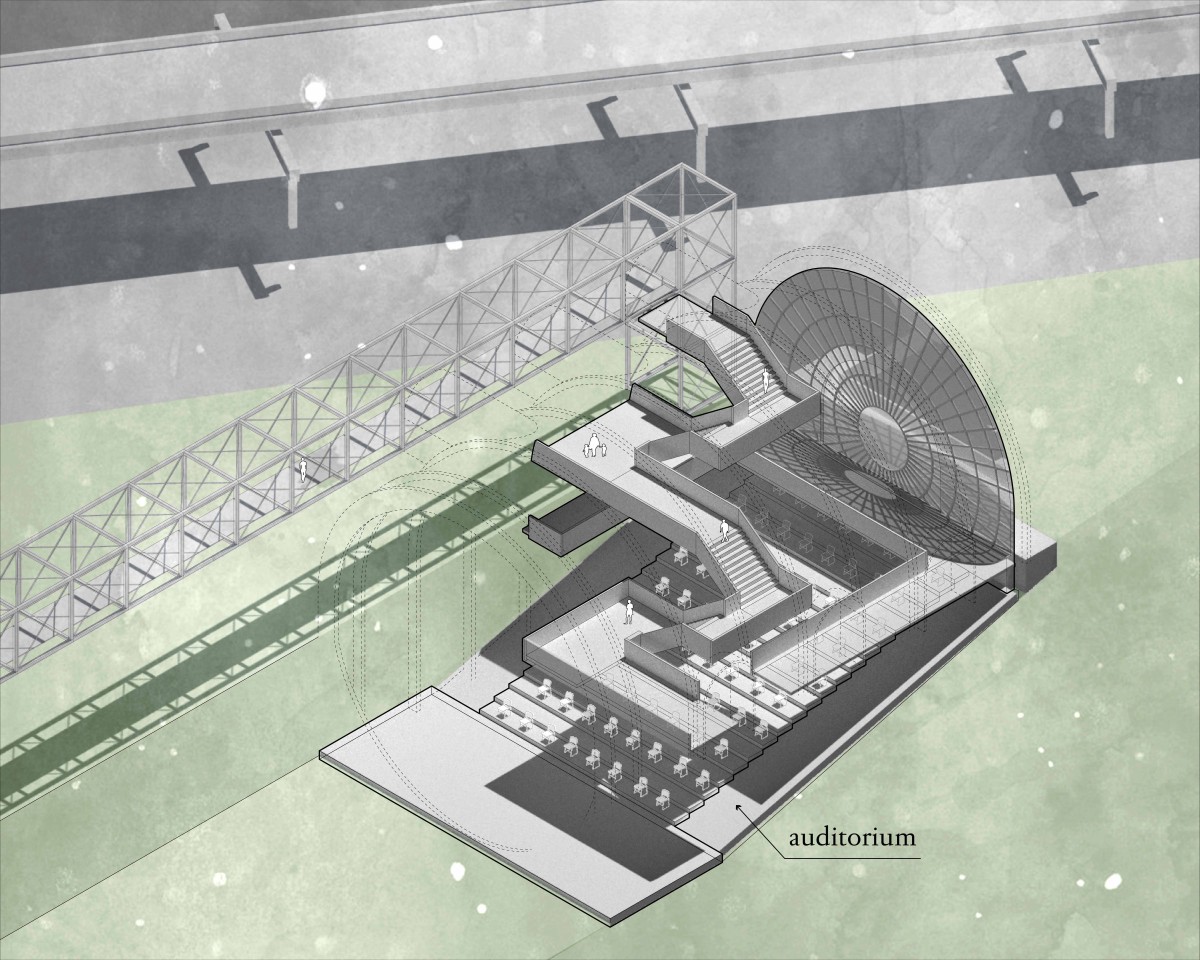

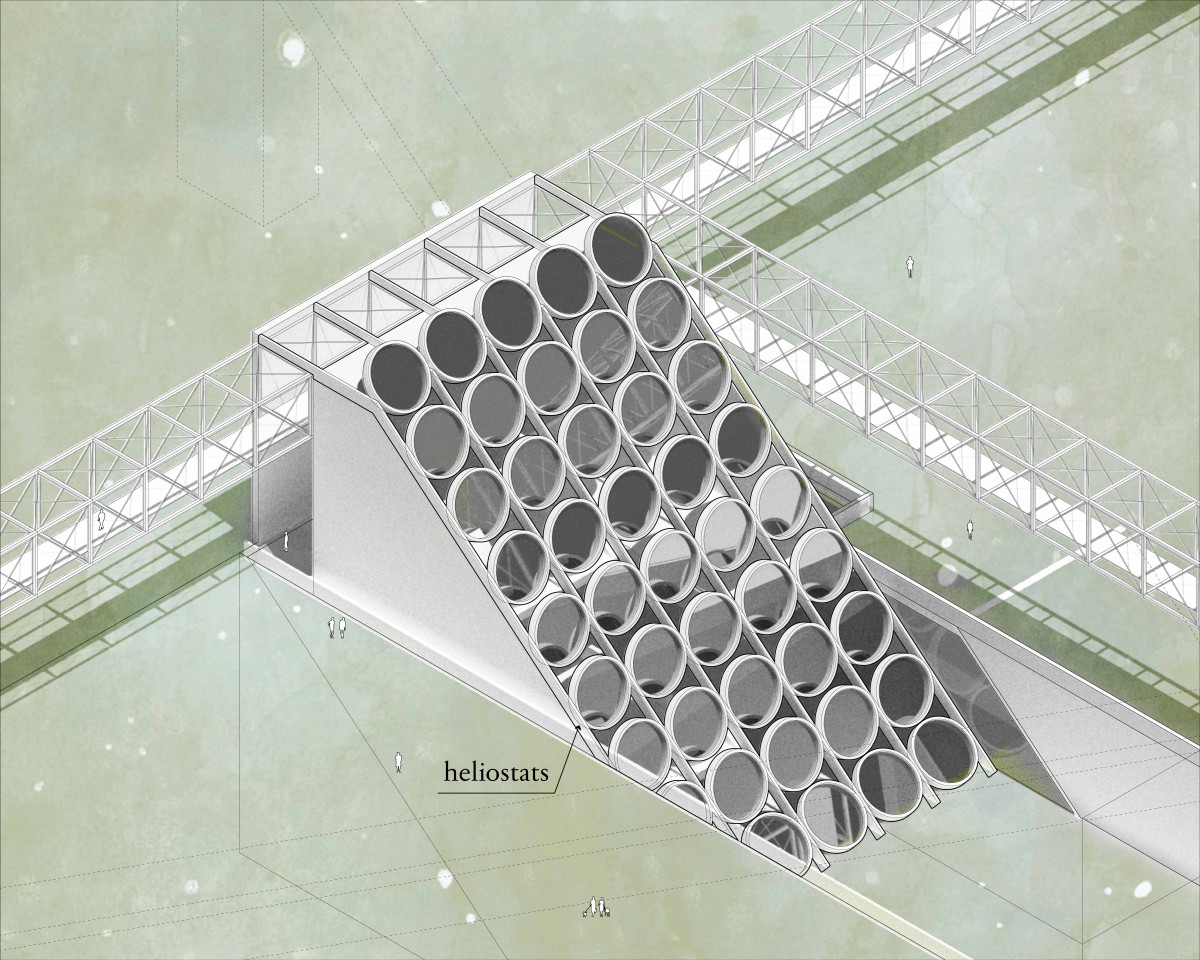

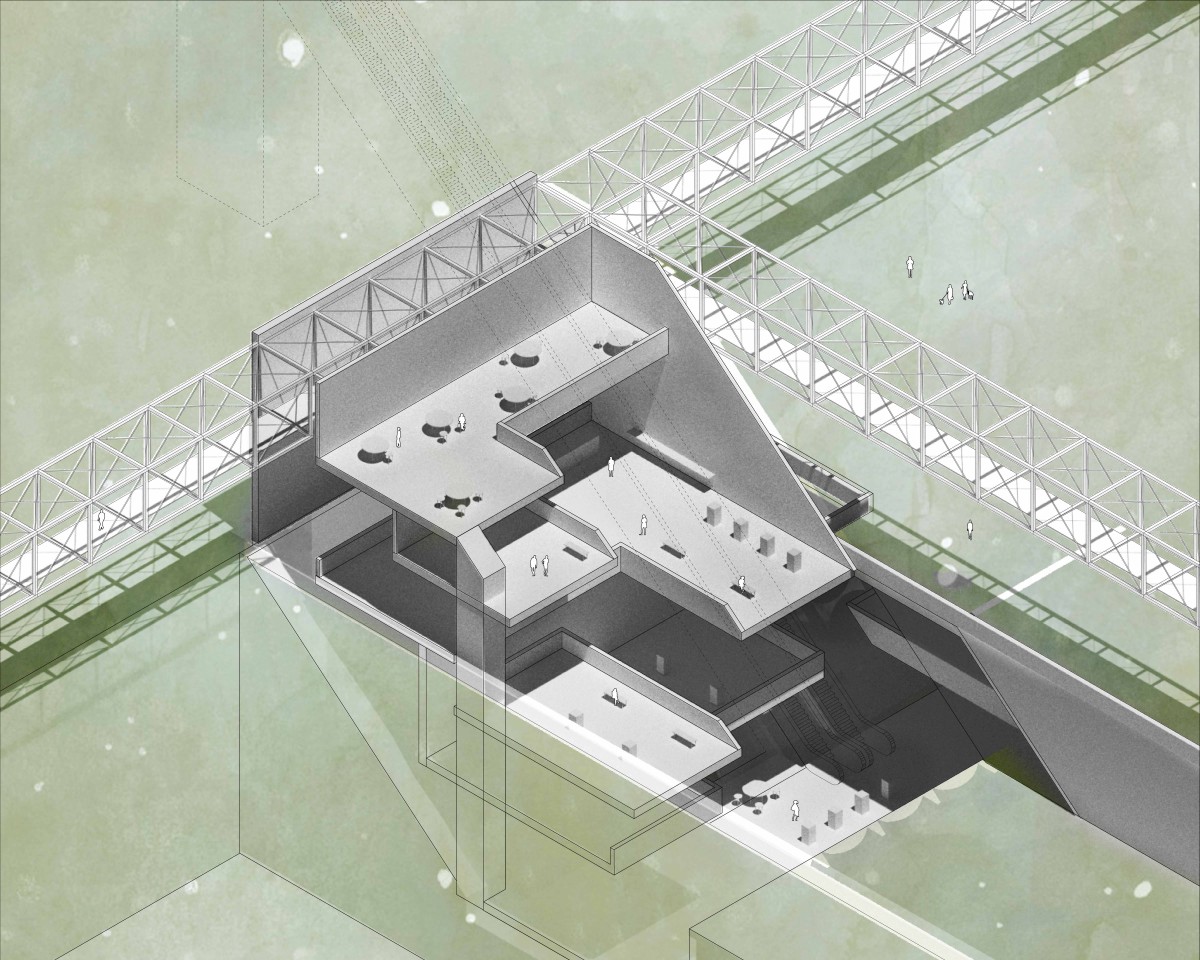

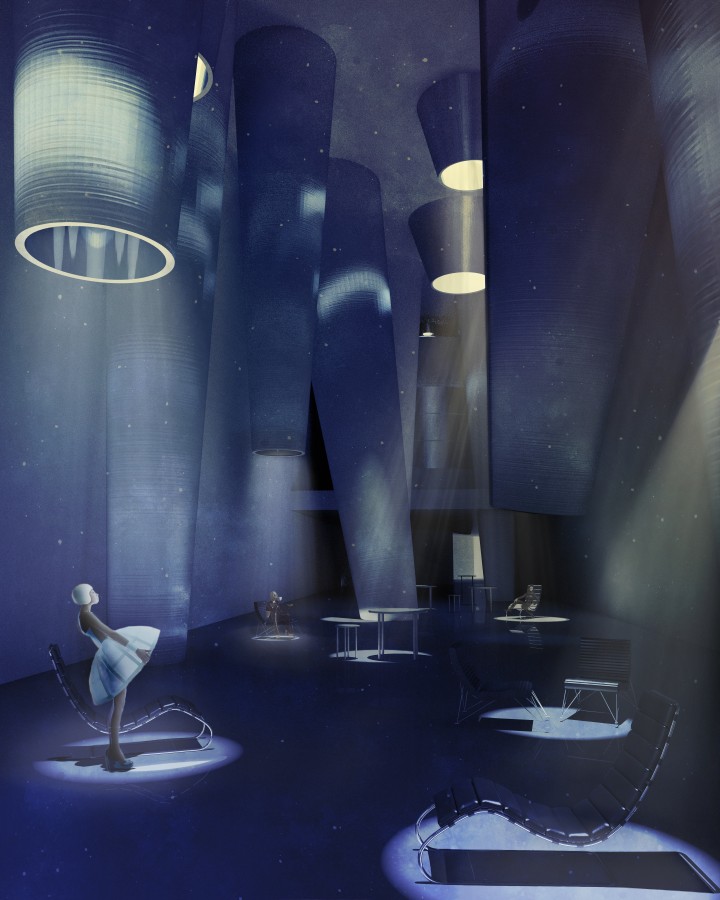

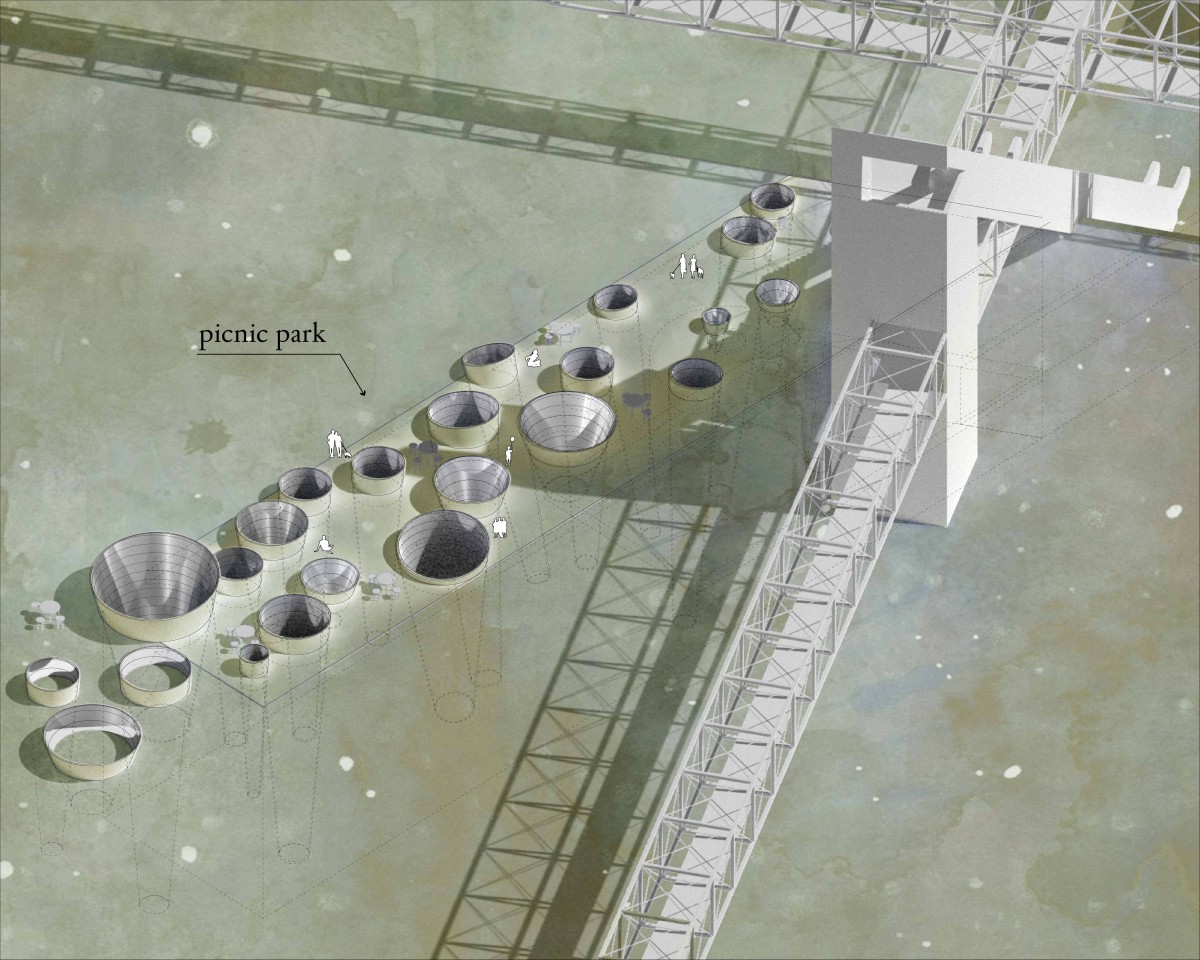

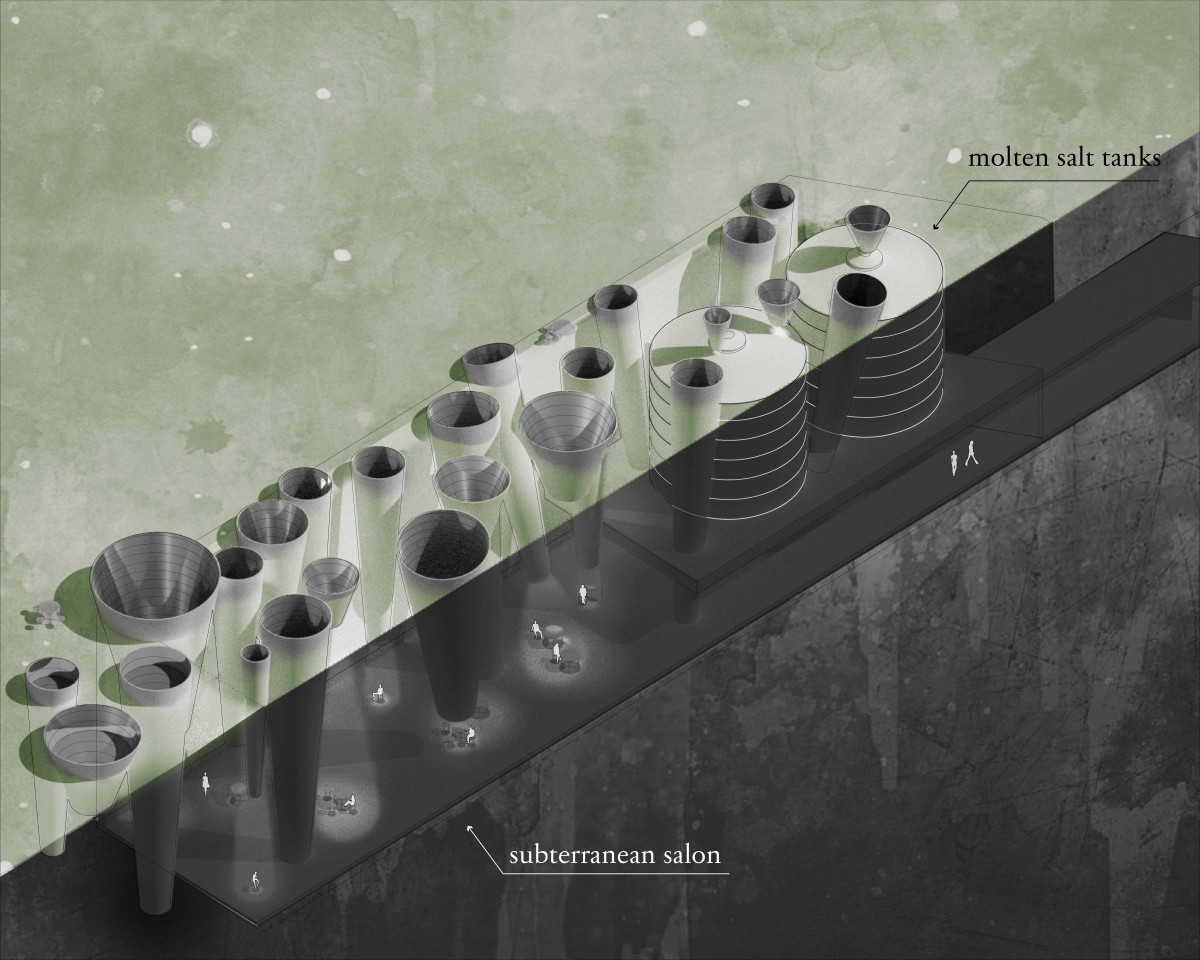

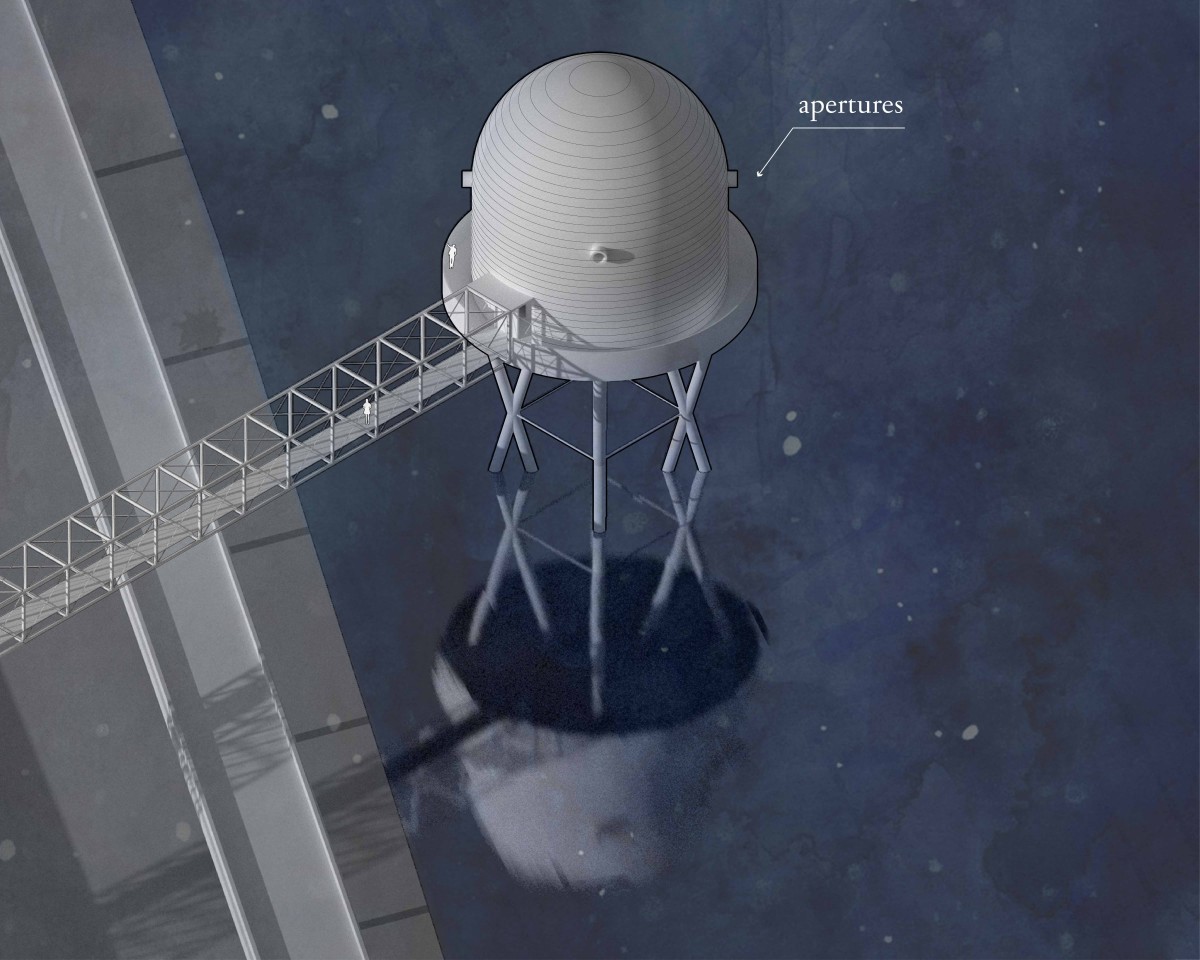

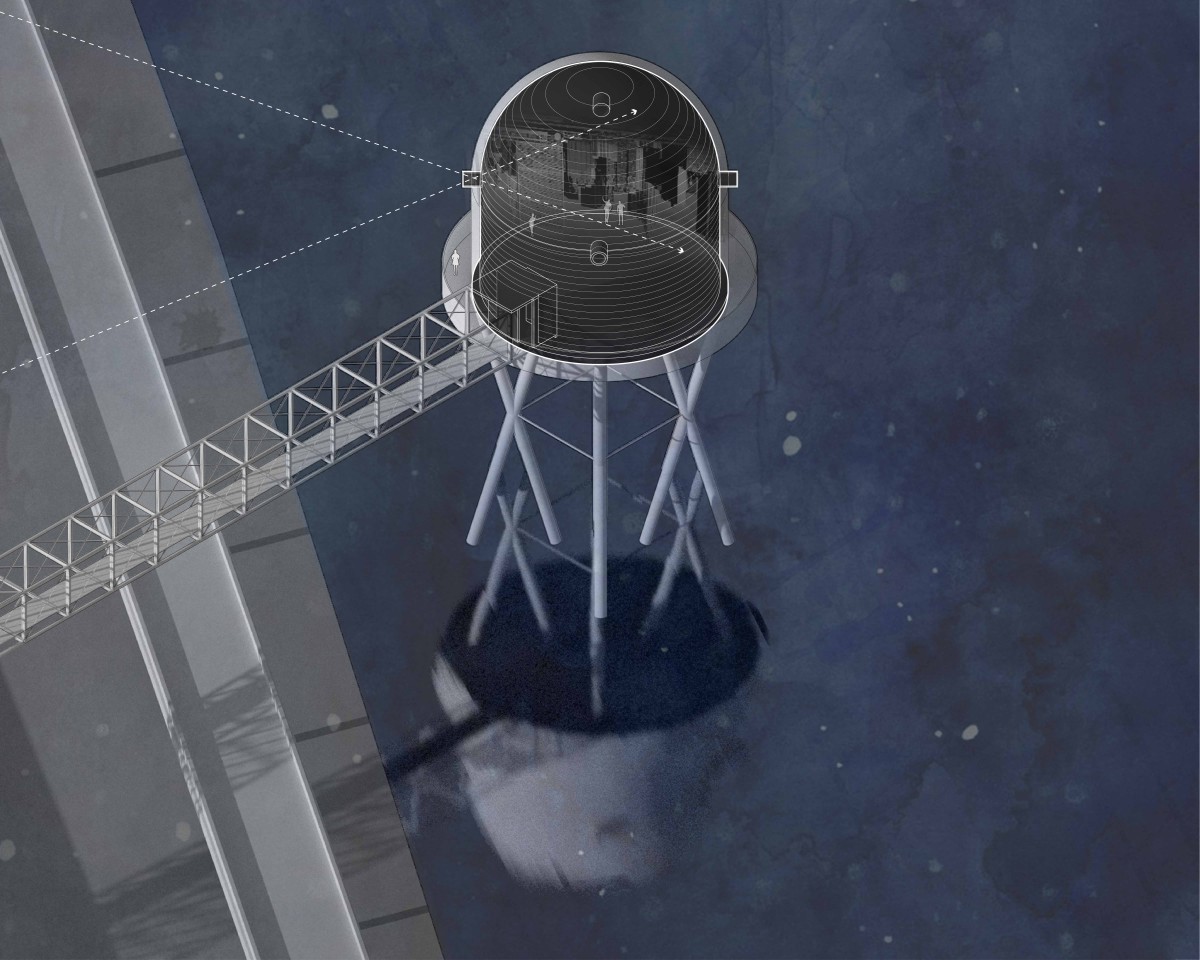

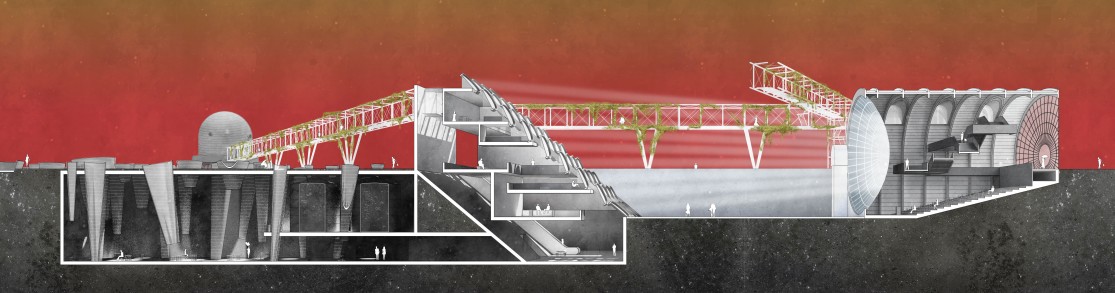

However, the WATT Center suggests an alternative. Recalling the site’s former function as a source of power and light, it proposes a center of solar energy, focused on the integration of public space, industry and art. As an anti-monument, it celebrates the non-celebrated; as a symbol of industry, it memorializes utilitarian design. Taking the form of a sundial, it changes constantly, allowing its guests to experience layers of time in a series of light space concentrators that integrate solar industry with public solitude. As a generator of dream spaces, it juxtaposes light and dark to create an upside down experience of the familiar city and awaken its guests from the pre-prescribed patterns of daily life through a total experience of light.

As the world is haunted by the lurking shadow of climate change, the subject of energy continues to be a central topic, and power plants continue to be key players. A focus on efficiency has led to a complete separation of energy industries from city infrastructures. This has pushed power plants to the countryside and allowed people to believe that they can simply flip a switch and the lights go on, like magic. However efficient this may be, it has led people to forget the true work involved in the production of energy and therefore its true value. This dissociation begs us to reconsider the future of electricity and our relationship with light. By architecturalizing industry through the integration of energy infrastructures and public spaces, architecture has the opportunity to design light to create dream spaces that encourage a more active engagement with experience as well as a more conscious consumption of light.

Famously known as the city of lights, New York was one of the early cities to be artificially illuminated. It now consumes an average of 11,000 Megawatt-hour per day and less than 1/4 of it comes from renewable sources. The historic Waterside Generating Plant, between 39th and 42nd St. on the East River, was one of its first steam power plants. What was once a center of energy, and a symbol of industry and technology, has now been decommissioned and completely demolished to make room for the development of what is planned to be more luxury residential towers.

However, the WATT Center suggests an alternative. Recalling the site’s former function as a source of power and light, it proposes a center of solar energy, focused on the integration of public space, industry and art. As an anti-monument, it celebrates the non-celebrated; as a symbol of industry, it memorializes utilitarian design. Taking the form of a sundial, it changes constantly, allowing its guests to experience layers of time in a series of light space concentrators that integrate solar industry with public solitude. As a generator of dream spaces, it juxtaposes light and dark to create an upside down experience of the familiar city and awaken its guests from the pre-prescribed patterns of daily life through a total experience of light.

Thesis Booklet: The WATT Center: Spaces of Light Magic